January 30, 2014

Economic Growth Linked with Poor Health

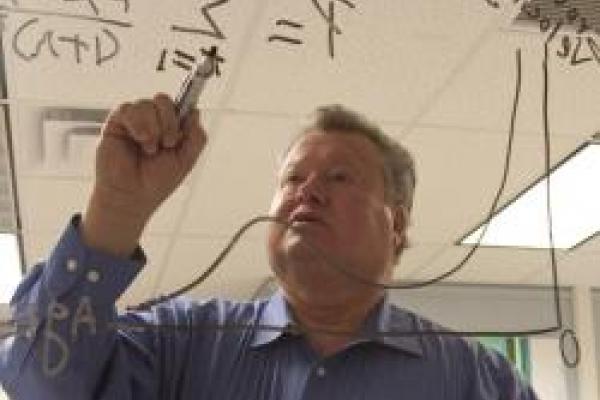

Richard Steckel, distinguished university professor of economics, anthropology and history, is author of a new study finding that the American surge in the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes is concentrated in the South and can be partially traced to the area’s rapid economic growth between 1950 and 1980.

By way of what researchers call the “thrifty phenotype” hypothesis, Steckel’s study suggests that economic conditions present during fetal development that then improve dramatically during a person's childhood lead to poorer health in adulthood.

“If the thrifty phenotype hypothesis is correct, people with diabetes today should have had a socioeconomic history of moving from poverty to prosperity,” said Steckel.

According to the hypothesis, pregnant women living in poverty influence fetal development by sending biological signals that adequate nutrition will be hard to come by in life. When children instead grow up under relatively prosperous conditions, their bodies can’t adjust, the study explains.

In the South, and particularly among African Americans, poverty was rampant for several generations until industrialization took hold in the 1950s and ’60s. When economic growth ensued, so did the region’s high prevalence of Type 2 diabetes. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in many areas of the South stretching from Oklahoma to West Virginia, more than 10.6 percent of the adult population had Type 2 diabetes in 2009.

Steckel, an expert on the economics of the South, obtained state per-capita income data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and, along with the diabetes figures from the CDC, constructed a statistical model to investigate the consequences of income change on diabetes prevalence, analyzing the ratio of per-capita income in 1980 to that in 1950 and those ratios’ relationship to the proportion of each state reporting Type 2 diabetes in 2009.

“It’s a clash between anticipated lifestyle and the lifestyle that’s realized,” said Steckel, explaining how improvements in income translate into the increased consumption of processed foods and sedentary lifestyle that increase a person's risk for obesity and other diseases.

That isn't to say other proven causes of diabetes are moot.

According to Steckel, his paper does not contradict studies that show proximate causes of diabetes.

“I'm just trying to back up behind those proximate causes and say this is the underlying mechanism: a socioeconomic revolution, a nutrition revolution and a 'derevolution' of exercise and work," he said.

“This is why socioeconomic data could be useful during a physical exam, in a way that could make preventive medicine more effective. You can probably identify the people most at risk for diabetes based on their socioeconomic history, and those are the ones clinicians should target."

Steckel’s theory supports findings from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the World Health Organization published last year comparing diabetes prevalence, food consumption and socioeconomic situations in 173 countries around the world.

Steckel’s research is published in the July/August issue of the American Journal of Human Biology and reported by Emily Caldwell, assistant director, Ohio State’s Research & Innovation Communications.